Jun-19-2014

Brazil & Paraguay - Transborder Journalism: Challenges, Difficulties and Needs

Marcelo Cancio

BA in Social Communication, PhD in Communication Sciences, Post-Doctorate Autonomous University of Barcelona / Spain, Professor at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul / Brazil

Support from: CAPES

e-mail: marcelo.cancio@ufms.br

Abstract

Many cities located along Brazil’s border with Paraguay generate information on a daily basis, with repercussions on both sides. News that is reported by the local media. This article reveals features of transborder journalism and the profile of journalists who are active in media outlets. The text also sets forth the challenges, working conditions, difficulties, risks and needs of those making journalism in a border region.

Keywords: Journalism; journalists; border; communication.

Introduction

In these border regions, the physical proximity of cities that are home to different people, languages, cultures and legislations provides constant dynamic communication between the populations. This framework blends economic, social, political, religious, environmental, urban and communication-related issues. In those places, along with daily interaction and cultural habits, there is a continuous process involving the conveyance of information through newspapers, news sites and local radio and television stations on either side of the border. This situation blends news conveyed in two different languages. Along the border, the daily challenge for journalists involves linking societies filled with contradictions comprising a blend of initiatives involving integration and conflict, friendship and rivalry, trust and mistrust. In this context, journalistic work is essential for relating neighboring populations. Understanding the social phenomenon unfolds requires historical and current references to the communities.

The Brazil-Paraguay border, which is filled with historical and war-related events, was defined only after many battles, diplomatic negotiations and a six-year war. Soares (1973, p. 258) recalls that “The demarcation of the border began on August 12th, 1872, where the Apa and Paraguay rivers meet. That demarcation was completed on October 24th, 1874.” Many authors have already researched social, economic and political issues involving the border. This study is centered on another valuable aspect that the border also offers: that of communication, especially the journalistic process and the work of journalists who are active in the region.

Transborder journalism

The countless relations forged between the two countries generate many media’s agendas. Both the Paraguayan and Brazilian sides continually produce events providing a wealth of information. Transborder journalism conveyed daily to the populations on either side creates a unique communication-related aspect. Besides disseminating local facts, such transborder journalism holds direct influence on the populations in those places. Zurita (2004) points to journalism made in a border area as being a factor for integration. To the author (2004, p. 64), “journalism is an instrument in service to integration among nations”. Journalism can certainly contribute toward integration and interaction processes. However, it must be pointed out that it works with complex social issues and, just as there are integration-related situations, so, too, do many conflicts take place. Journalism acts on both ends, as such factors cover journalistic procedures.

Making journalism along a border region comprises features which somehow cause it to stand out from other regions. It doesn’t end up being different in format, but in the way close neighbors are understood. In transborder societies, there is a duality that does not occur anywhere else. Along the border, information interest on either side could clash. There has to be a broad vision so that the information is of value for both societies. An incorrect piece of information published on one side could be quickly rejected on the other side, thereby creating a situation of international friction. According to Luisa Portugal (2004, p. 100), “making journalism along a border area is an arduous task, doubly complicated and of extreme responsibility, because our messages most often usually easily and involuntarily erupt on the “other side of the border,” and, at times, upsetting one’s neighbor”. Transborder journalists do not have an easy task to achieve, as they require knowledge on their own country and of what is ahead of them. In the case of professionals working along the Brazil-Paraguay border, there are other factors that could interfere in their action: the risks, the danger of the region, the threats and other forms of violence affecting them. An example was the testimony from journalist Paulo Rocaro. In an exclusive interview, he commented on the violence that takes place along the border against journalists. At that time, he was chairman of the Ponta Porã Press Club. Rocaro (2007) reported as follows:

“Along the border region, we have many leaders, whether in the criminal underworld, or in the business sector, in politics, still with an interior and “colonelist” mentality, in the use of physical force, moral bullying, political persecutions and press professionals are subject to all this. A topic none too pleasing to a politician, a drug dealer or a gunman, the press professional will inevitably be brought to account for that. Here, there is bullying, there are death threats, persecution and executions of professionals.”.

Rocaro seemed to predict what would happen to him later on, as, in February 2012, the journalist was assassinated by two gunmen in Ponta Porã. It took police over a year to investigate the journalist’s death, and so, in 2013, they announced that there were political interests behind the murder. Cases of violence against journalists repeat themselves along the border and, in fact, this is a dangerous region for journalistic work. Still, even with the problems and the risks involved with their line of work, many professionals work along the border, performing notable journalistic duties. In the meantime, little is known of their professional challenges, needs and difficulties.

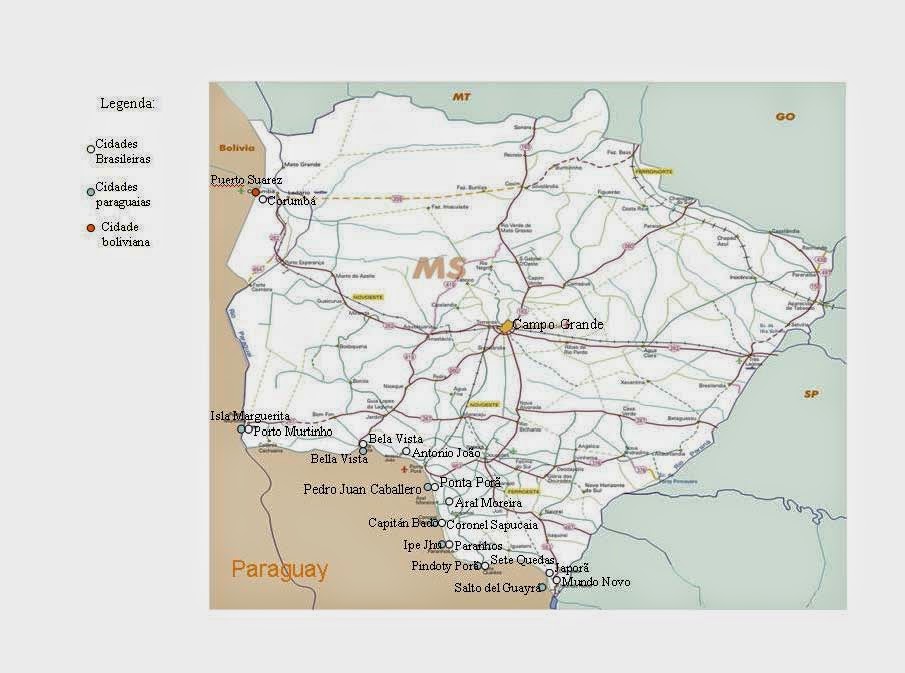

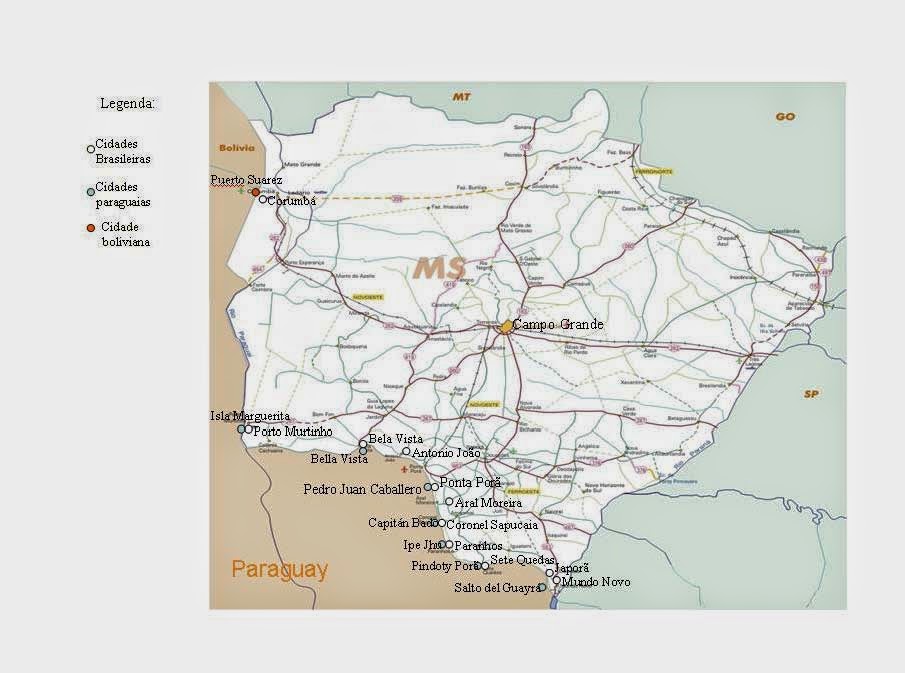

Border research

This study was conducted during the year 2012 with professionals from 14 cities arrayed along a border over one thousand kilometers long separating the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, from Paraguay. The lack of natural obstacles eases the circulation of people, trade relations and a ceaseless exchange of information. The cities that were visited for conducting the research included: Mundo Novo, Japorã, Paranhos, Sete Quedas, Aral Moreira, Bela Vista, Ponta Porã and Porto Murtinho, on the Brazil side, and Salto Del Guayrá, Ype Jhu, Pindoty Porã, Pedro Juan Caballero, Isla Margerita and Bella Vista Norte, on the Paraguay side, as shown on map 1.

Map 1: Cities on the border between Mato Grosso do Sul (Brazil) and Paraguay

http://www.mapas-brasil.com/mato-grosso-sul.htm

The universe used for the analysis comprised the journalists who live and work in those cities, regardless whether or not they have any academic education in Journalism or in any other field of communication. Their professional performance and the role they play in the local media of these cities were taken into account. The methodology established prior phone contact with the journalists, trips to the towns and cities, visits to companies, personal interviews and working with questionnaires. The data requested included name, age, gender, country of birth, city where they live, workplace, language spoken and level of education. The journalists also answered open-end questions regarding the production of news on the neighboring country, their main work-related difficulties and educational needs.

Results

A research that sought to reveal journalists’ work in areas close to international borders provides a large amount of data regarding the profession itself and of the activities carried out in such a complex region. A research such as this had not been conducted in that area with Brazilian and Paraguayan journalists. The results shown reveal data of questionnaires replied to by 63 professionals from 43 media companies. As shown in table 1, 44 Brazilian and 19 Paraguayan journalists spontaneously took part.

Table 1: border cities and the number of journalists in each.

|

CITIES |

JOURNALISTS |

|

Japorã (Brazil) |

2 |

|

Paranhos (Brazil) |

2 |

|

Sete Quedas (Brazil) |

2 |

|

Mundo Novo (Brazil) |

4 |

|

Aral Moreira (Brazil) |

3 |

|

Bela Vista (Brazil) |

9 |

|

Ponta Porã (Brazil) |

19 |

|

Porto Murtinho (Brazil) |

3 |

|

Salto del Guayrá (Paraguay) |

1 |

|

Pindoti Porã (Paraguay) |

1 |

|

Ype Jhu (Paraguay) |

3 |

|

Pedro Juan Caballero (Paraguay) |

6 |

|

Isla Marguerita (Paraguay) |

5 |

|

Bella Vista Norte (Paraguay) |

3 |

A piece of information that was sought and obtained in the research was the age group of journalists in that border region. Most of these professionals are over age 30, as shown in table 2. This information somehow indicates that the journalists have quite a bit of professional experience.

Table 2: age of journalists

|

AGE GROUP |

JOURNALISTS |

% |

|

Under age 36 |

17 |

26,9% |

|

Ages 36 to 45 |

18 |

28,5% |

|

Over 45 |

20 |

31,7% |

|

Did not say |

8 |

12,6% |

The research also revealed the gender of the professionals who are active at the companies that were visited. A surprising piece of information is the large percentage difference between men and women working in the border media market. Most professionals researched are males, as the figures for table 3 show.

Table 3: gender of journalists

|

GENDER |

JOURNALISTS |

% |

|

Male |

51 |

80,9% |

|

Female |

12 |

19,1% |

Three languages predominate along the border between Mato Grosso do Sul and Paraguay: Portuguese, Spanish and Guarani. That’s why journalists in that region master more than one language. Despite interacting along the border, most Brazilian journalists speak only Portuguese. Many Paraguayan journalists speak more than one language, as they are generally the ones who master Guarani, the indigenous language. This can be seen in table 4.

Table 4: Languages spoken by journalists

|

LANGUAGES |

JOURNALISTS |

% |

|

Portuguese |

23 |

36,6% |

|

Spanish |

2 |

3,1% |

|

Portuguese and Spanish |

21 |

33,4% |

|

Spanish and Guarani |

2 |

3,1% |

|

Portuguese, Spanish and Guarani |

15 |

23,8% |

An important piece of information obtained through the research was the level of education of border journalists. Because they are based in small towns and cities far away from cities where universities are located, most of them still don’t have access to university centers. The result is that many professionals worked at media outlets with an average level of education and without concluding studies in higher learning. Generally speaking, they begin their activities with transborder media because they are offered work opportunities according to good writing or speaking skills for communicating, especially at radio stations. They learn journalism in their daily practice at editorial departments. The level of education of these professionals is shown in table 5.

Table 5: journalists’ level of schooling.

|

LEVEL OF EDUCATION |

JOURNALISTS |

% |

|

Basic |

2 |

3,1% |

|

Middle Schooling |

26 |

41,3% |

|

Higher learning, incomplete |

15 |

23,9% |

|

Higher learning, concluded |

18 |

28,6% |

|

Did not say |

2 |

3,1% |

As for the workplaces of border journalists, it was noticed that most of them are active at radio stations, which predominate in this region. One of the reasons explaining this situation is that radio still constitutes a predominant media outlet along the border. There are many possibilities for obtaining a public concession, as it costs less to set up a radio station than to set up a television station or presses for printing newspapers. Though news sites are starting to become more operated by journalists, they still do not attract enough advertising revenues to support them. The workplaces and the number of professionals in each are shown in table 6.

Table 6: places where journalists are active.

|

MEDIA OUTLETS |

JOURNALISTS |

% |

|

Radio |

30 |

47,6% |

|

Press Relations |

6 |

9,5% |

|

Site |

5 |

7,9% |

|

Newspaper |

14 |

22,2% |

|

Television |

3 |

4,7% |

|

More than one medium |

5 |

7,9% |

In the questionnaires, a few questions were asked regarding occasional issues, such as difficulties at work, work-related and educational needs, difference with regard to making journalism in a border region and how often topics on the neighboring country are produced. Despite a wide variety of answers given, they allowed for analyses that reflected the perception of professionals regarding their own work. With regard to difficulties experienced for exercising journalism in the border region, 54% of interviewees cited the following items: unsafe, drug trade and no freedom of expression. As common shortcomings in their work, they also pointed out the obtaining of precise information because of the languages spoken; a lack of more professionals at editorial departments and the need for a better physical structure of media outlets. Ethical issues, more travel possibilities when producing news reports, communication with the neighboring country and a lack of vocational training were other difficulties cited by the interviewees.

Under the item pertaining to work-related needs, 50% of interviewees pointed out a greater qualification of journalists who are active in the border region as a priority. They refer to specific vocational training courses. Other work-related needs given included: better structure for companies; knowledge of languages; appropriate remuneration; job openings and the hiring of staff; greater professional enhancement and greater freedom of expression.

When asked regarding educational needs, they all cited elements pertaining to improved training of journalists. The item most widely cited by professionals was the implementation of a degree in communication/journalism along the border region. In more specific training initiatives, they mentioned and suggested several courses, including language(s), speech, diction, photography, radio, editing, marketing and sales, management and planning, editorial work, information technology (IT), oratory, legislation, investigative journalism, printing layout, video and reporting. Also mentioned were vocational programs in general on regional knowledge and post-graduate study programs.

When questioned as to whether making journalism is different, 80% of interviewees said yes, 12% said there was no difference, and 8% did not answer that question. Most stated that the biggest difference consisted of getting to know the culture of two countries. The second most widely mentioned item was the biggest difficulty in the journalistic process (agenda, verification, editorial work, publication and ethical issues) related to topics involving both countries. Other reasons pointed out included life-threatening/unsafe circumstances; languages; influence of trafficking/drug trafficking; a small number of professionals; integration between borders; contact with controversial topics; diplomatic and legislative issues and the responsibility of being a more courageous professional than in other places.

With regard to producing information linking both countries, most journalists (90%) said they had produced news on the neighboring country. When asked how often they produce such information, the figures change. 35% of journalists said they do that on a daily basis. Another 35% said they produce weekly and another 13% responded that they publish twice or three times a week. 17% did not answer that question.

Final considerations

The data given as part of the research show important information regarding professionals who are active in a specific border area as well as the work performed by them, with all the risks and difficulties this region comprises. It was possible to outline a profile of these professionals and gain some knowledge of what they think regarding their profession and the difficulties in their activity. With more or less efficiency and with more or less criteria, border journalists do a job that allows border populations to become aware of what is happening on either side of the border. This activity is vital for border society because of the exchanges and links that can be achieved between the societies of each country. It carries considerable social weight, but which, generally speaking, is not highly appreciated from the standpoint of recognizing media companies and, at times, by the very border society itself. The research contributed toward listening, providing a voice and enhancing these professionals. To unveil their difficulties and needs and to try to encourage them to develop better communication work that can reflect on the contents of the information to be received by the populations of border cities.

References

Books

PORTUGAL, Luisa (2004). Periodismo de Frontera: Un Proyecto Para la Paz. Peru-Ecuador. Piura (Peru): Universidade de Piura.

SOARES, Teixeira (1973). História da Formação das Fronteiras do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército-Editora.

ZURITA, Robson William Paredes (2004). Aproximación al Concepto de Periodismo Transfronterizo. Piura: UDEP.

Internet

Guia Geográfico. Mapas do Brasil. Retrieved 18.06.2014 from http://www.mapas-brasil.com/mato-grosso-sul.htm

Interview

«Paulo Rocaro - Exclusive Interview» (March 2, 2007). Ponta Porã / Brazil.

Published by Marinho Media Analysis / June 19, 2014

http://www.marinho-mediaanalysis.org/2014/06/brazil-paraguay-transborder_19.html